As kids, my sister and brother and I would play with the old "doughboy" helmet that was in the garage. I doubt if we made any connection with the Great War. It was simply a toy that we used when we staged our own backyard conflicts. I rarely heard my father talk about his war experience, and when he did, I was too naive to recognize its significance. I should have been taking notes.

As I eventually gained an interest in my family's history, I certainly wanted to include a detailed understanding of my father's military experience. So, in the mid-1980's, I corresponded with the U.S. Army and the Veteran's Administration to get any documentation that might be available. My father had died in 1971. I was shocked to learn that none of his war records existed. In July of 1973, a disastrous fire had destroyed much of the National Personnel Records Center outside of St. Louis. Over 80 million folders of official military records were destroyed. There were no backups or duplicates. My father's military history had gone up in smoke. I resigned myself to the notion that I would never know the details of his service -- when and where did he serve, what units was he associated with, what battles had he witnessed? I would never know. I recall the enormous disappointment when I received the news from the Government that the records no longer existed.

But then came the Internet and the World Wide Web. And along came better and better search engines. And perhaps even more important, people and companies scanned and digitized huge quantities of documents that had been residing in libraries and private collections for decades. More and better information was becoming accessible and searchable on the Internet. That combination of developments has made much of my father's war record available in spite of the devastating fire that had destroyed so many documents.

The first breakthrough occurred a few weeks ago when I discovered an article in a little-known journal entitled "The Journal of the Association of Military Dental Surgeons of the United States." In the July, 1919, issue of that journal is an article entitled, "Dental History of the Second Division, A.E.F." by Lt.Col. George D. Graham. Early in the article, Colonel Graham mentions that he took command of the dental unit described in March, 1918, and lists the officers then in the dental unit. My father was one of those mentioned. Thanks to the library at the Northwestern University School of Dentistry and to Google's efforts to scan and digitize academic journal collections, I now know which organization my father served in during the war.

|

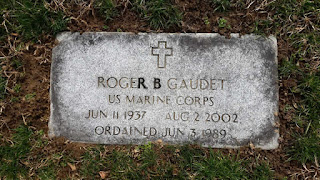

| One of my father's units was the 9th Infantry Regiment of the 2nd Army Division of the A.E.F. |

This article goes on to describe the history of the unit and its operations from March to November of 1918. Within those few months, they saw action at Chateau Thierry, Soissons, St. Mihiel, the Champagne Front, and the Argonne. My dad was definitely in the thick of the battles that were taking place. The article also describes how the Dental Corps personnel were engaged, often acting as anesthetists for the medical corps during surgery. Dr. Graham states, "Dental officers were installed in towns, in which troops were temporarily billeted, in dugouts, in tents and occasionally by the roadside, wherever their organizations happened to be, often under shell fire." He also describes how, under these field conditions, these oral surgeons were developing better, lighter, and smaller instrument packages and equipment packages to make it easier to relocate and set up their "offices." I also learned from Dr. Graham's article that in October, 1918, my father was "evacuated, sick" along with two other dentists. No further detail is provided on either the nature of the sickness nor the destination of the evacuation.

Not too long after I located Dr. Graham's article, I found another offbeat publication, "Dental Cosmos, A Monthly Record of Dental Science." This gem had been scanned by Google from within the Health Sciences Library at the University of California, Davis. Again, I extend my thanks. Volume 59, dated November 1917, informs us that during the week of September 22, 1917, a certain Army reservist named Harold R. Mead was assigned "To Camp Mills, Garden City, Long Island." So now, I knew where my father completed his training prior to going to Europe. The pieces of the puzzle were appearing slowly but surely.

On the U.S. Army Medical Corps site, I discovered a sizeable document called "A History of Dentistry in the U.S. Army to World War II." In Chapter 15 of that work I read the following, which bears tribute to the service of men like my dad:

"The dental service that Robert Oliver and his colleagues built in France experienced its most difficult test with the combat divisions of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF). Never before in the history of the Army or its medical department had dental officers gone directly into battle as part of a combat unit. Thanks to Oliver’s efforts and those of many others in the Dental Corps, the AEF had dental officers and assistants attached to all of its front line divisions, including infantry and engineer battalions in the trenches and field artillery batteries. Without the experience of any army in history to guide it, the AEF integrated the dentists into the fabric of the division in a variety of ways. While they were sometimes assigned collateral duties with little regard for their professional backgrounds, they were more often employed as auxiliary medical officers to assist the battalion and regimental surgeons and medical detachments on the battlefield. Regardless of their assignments, the dental officers and their assistants served their fellow soldiers in times of trial, a number of them winning awards for gallantry on the battlefield and others sacrificing their lives. Their performance ultimately won the soldiers’ respect and the honored place in the Army Medical Department that dentists had so long sought."

A search of newspapers of the period when my father likely would have returned revealed another gem. On August 5, 1919, the following article appeared in the Schenectady Gazette:

"DR.

MEAD, FIRST LOCAL DENTIST IN FRANCE, IS HOME

Dr. Harold R. Mead of 6 Eagle

Street, the first Schenectady dentist to reach France, has returned, almost the

last local practitioner to leave that country. Dr. Mead enlisted in July, 1917,

and was commissioned first lieutenant in the same month. He spent five weeks in

Camp Mills and was then sent overseas, where he remained for 21 months.

He was assigned to the second

division and spent most of his time with the 9th and 23d Infantry, composed of

both Infantry and marines. Part of his experience was behind the lines with the

medical detachment, and part of the time was spent at the front In first aid

work. After the signing of the armistice he resumed the work of dentistry.

Among the engagements in which Doctor Mead took part were that of Chateau Thierry, St. Mihiel, and the Meuse-Argonne. His division was the American unit which aided the stopping of the German drive on Paris. At the time of one German raid on his regiment, in which one of the doctors and seven Red Cross men were taken prisoners and another doctor-captain wounded, he, together with three others, was all that was left of the medical detachment. These four were forced to do the work of 12 or 13 men in giving first aid to the wounded and sending them behind the lines. He was commended for this work. Dr. Mead tells an amusing incident which came to his notice while in service. One of his fellow practitioners, while working on a patient in his office chair, had the front of his office blown away by a shell. The patient "got up and ran" and was never heard of since.

Among the engagements in which Doctor Mead took part were that of Chateau Thierry, St. Mihiel, and the Meuse-Argonne. His division was the American unit which aided the stopping of the German drive on Paris. At the time of one German raid on his regiment, in which one of the doctors and seven Red Cross men were taken prisoners and another doctor-captain wounded, he, together with three others, was all that was left of the medical detachment. These four were forced to do the work of 12 or 13 men in giving first aid to the wounded and sending them behind the lines. He was commended for this work. Dr. Mead tells an amusing incident which came to his notice while in service. One of his fellow practitioners, while working on a patient in his office chair, had the front of his office blown away by a shell. The patient "got up and ran" and was never heard of since.

The doctor was one of about

seven who left this city to practice dentistry in the service. He has a

brother-in-law, Captain Gilbert L Van Auken, who spent about the same time as

the doctor in the field artillery. He has always lived in this city and expects

to resume his practice in a week or two at his old location in Crane

Street."

He spent 21 months overseas. It's remarkable to me that he rarely spoke of these times. One of the few stories I recall him telling was of going into Paris once on leave with another officer. Meat was in short supply, so a restaurant would usually offer a single choice of meat each day. On this particular day and at the restaurant in which my father found himself, the meat of the day was tripe. My dad said that they told the waiter to give their meat to a nearby French couple. He had tasted tripe and said it was the worst thing he ever put in his mouth. The French couple was overtaken with emotion that the Americans had "sacrificed" their meat to the benefit of the French. Little did they know...